HERE'S A STORY about a lucky pocket knife, a drunken monkey and how war can change you forever.

When Livermore's Sally Trautwein graduated from college in 1962, she went to work for the American Red Cross at an evacuation hospital in South Korea. Her experience was similar to the movie "MASH," she said, "without the war part."

Although Trautwein avoided war in both Korea and in her next assignment in Japan, she was about to encounter the perils of war in Vietnam when she was asked to help set up a Red Cross program in a new field hospital.

Although Trautwein avoided war in both Korea and in her next assignment in Japan, she was about to encounter the perils of war in Vietnam when she was asked to help set up a Red Cross program in a new field hospital."It was early in the war, and I was young and fearless," she said. "I agreed to go."

Trautwein recalls taking a cab to retrieve mail in Saigon. "I was daydreaming," she said, "when I suddenly noticed we were headed away from Saigon toward the Cholon district."

Remembering that a week earlier an American had been kidnapped and held for ransom in the district, Trautwein asked the driver to turn around. He refused and started driving faster. Realizing she was being kidnapped, Trautwein pulled out a pocket knife a sergeant had given her in Japan. Still, the driver ignored her, even as she held the knife to his throat.

"In that moment, I had an epiphany," she said. "I was capable of doing bodily harm to another human being if my life were threatened. I nicked his neck."

At the sight of his blood, the driver slammed on the brakes. Trautwein jumped out and "ran like the wind."

Another brush with death came in the backyard of the villa where she lived with nurses and doctors next to the hospital. Helicopter pilots lived next door, and because the pilots were at risk of attack, an armed American sentry always stood watch.

Trautwein acquired a pet spider monkey that was an alcoholic.

"If we had evening cocktails, the monkey would grab our glasses and finish off our drinks," she sai

d. "It didn't take long for him to get drunk."

d. "It didn't take long for him to get drunk."One night after the monkey passed out, Trautwein carried him out back to put him to bed in his banana tree. Wearing a very visible white blouse, she heard the sentry yell, "Halt!" She also heard him cock his rifle.

"Instinctively, I ran and dove through the screen door and across the tile floor," she said. Sure enough, he fired, just missing Trautwein and putting a bullet in the building.

"These young kids were scared to death and would shoot before finding out who was there," she said. "We saw many soldiers wounded or killed by friendly fire."

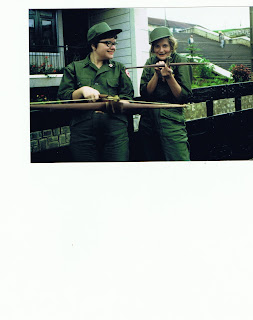

Trautwein nearly encountered death a third time in Vietnam when traveling on a helicopter, which she took a picture of (see below). Here is the story in her own words:

.

"The third incident came when the commanding officer of the hospital where I was working came to me and said I'd been working too hard and he had arranged for me to have a weekend in Dalat, which was a former French resort in the mountains.

.

The commanding officer told me to go to the airport where a plane would take me to the Dalat.

The commanding officer told me to go to the airport where a plane would take me to the Dalat.

.

The plane turned out to be Air America, the CIA airline. The two bush pilots were drinking out of paper cups and it wasn't coffee. These guys took incredible risks and were all crazy. We took off, stopping once to land on a dirt runway where we picked up fleeing Vietnamese peasants with chickens in tow.

.

After a nice weekend in Dalat, I hitched a ride back with a helicopter pilot I knew from the group who lived behind us. He had a reputation as the worse pilot around. It was me, the pilot, the flight surgeon who had never flown before, an old seargent and some kid with a machine gun.  .

.

.

.I sat in the back on a wooden box with ear phones on. It was a cloudy, damp day. We weren't in the air more than 45 minutes when over the phones I heard a jet pilot screaming obscenities and announcing that we were in the middle of his mission. Down on the ground were some Viet Cong troops he was trying to drop napalm on. Of course the people on the ground couldn't touch the jet with anti-aircraft fire because it was too high up. But we were at just the right altitude. .

The Viet Cong started firing. I heard a shot ping on the under belly of the chopper. .

'What am I sitting on?' I asked the seargent. .

'The ammunition, Ma'am' -- he replied. .

Oh great, I thought, my butt is going to be blown to Tokyo! We managed to make it back in one piece, but I asked the commanding officer to never again send me on a vacation!

.

There were lots of frightening moments. The Viet Cong were always bombing restaurants that the Americans frequented. To this day I still don't like sitting with my back to a door. Little old ladies with Viet Cong sympathies would walk up and hand you a loaf of bread with a hand grenande in it. After all these years, I still don't like loud noices. I still occasionally have a flash back, although not nearly as often as when I first came back. The night we invaded Iraq I wanted to put a pillow over my head. "

.

.

There were lots of frightening moments. The Viet Cong were always bombing restaurants that the Americans frequented. To this day I still don't like sitting with my back to a door. Little old ladies with Viet Cong sympathies would walk up and hand you a loaf of bread with a hand grenande in it. After all these years, I still don't like loud noices. I still occasionally have a flash back, although not nearly as often as when I first came back. The night we invaded Iraq I wanted to put a pillow over my head. "

.

Trautwein, who today makes her living as a real estate agent in Livermore, says her experience in Vietnam changed her.

"I don't take things for granted," she said. "When I was there I promised that if I survived, I would give back to others and appreciate every day of freedom I have."

In fact, Trautwein has given back, having served 10 years on a school board and now as a volunteer with Wardrobe for Opportunity and Operation Dignity.

Today's wars in Iraq and Afghanistan bring back memories.

"I still remember all those young boys whose hands I held, whose brows I wiped," she said. "I still pray that it won't be necessary to send any more."

"I don't take things for granted," she said. "When I was there I promised that if I survived, I would give back to others and appreciate every day of freedom I have."

In fact, Trautwein has given back, having served 10 years on a school board and now as a volunteer with Wardrobe for Opportunity and Operation Dignity.

Today's wars in Iraq and Afghanistan bring back memories.

"I still remember all those young boys whose hands I held, whose brows I wiped," she said. "I still pray that it won't be necessary to send any more."