When Cathy Ayelevi Forson Sjogreen was growing up in Ghana, her parents couldn't afford to send her to high school, so she earned money for her education by selling produce in an open-air market from a tray atop her head.

“I love learning,” said Sjogreen, 40, who speaks ten languages and whose first memory of school is sitting under a tree with other students. “We were taught according to the old British system.”

Today, Sjogreen, who lives in Livermore with her Swedish mathematician husband and their two young sons, hopes to one day return to her country of birth.

“When my husband first got his job with Lawrence Livermore Lab,” Sjogreen said, “my boys and I stayed in Sweden so I could finish my degree at Stockholm University.”

But the boys missed their father so much that Sjogreen moved the family to Livermore six months later, arriving in 2004 with her degree unfinished.

The oldest of seven children, Sjogreen has a special talent for learning languages. While a young woman in Ghana, Sjogreen used her language skills to land a job. Then, over time, her aptitude—and the generosity of a supervisor who paid her air fare—opened the door for Sjogreen to move to France, where she initially lived with an uncle.

"I admire everything about France,” she said, “its language, history, literature, and culture.”

Sjogreen lived in several French cities and worked as an interpreter and bilingual secretary. She also volunteered as a translator in hospitals, airports, train stations, and churches.

Always eager to enhance her language proficiency, Sjogreen was taking an advanced course in French in the early 1990s when she met her future husband, Bjorn.

“He was working on his post doctorate project,” she said. “It took me almost a year to agree to move to Sweden, because I still had my job, my relatives, and my good friends in France.”

Love, of course, won out, and Sjogreen moved to Sweden in 1994.

Now, 12 years and two children later, she hopes to finish her undergraduate degree at the University of California, Berkeley. In the meantime, she is attending Las Positas College.

“My intended major is French Literature,” she said, “but I’m curious about languages and wish to do more research in the field.”

While Sjogreen’s near-term goal is to complete her formal education, her eyes soften when she talks about Ghana and the 120 children her parents care for in the orphanage she helped them start in 1992.

“Each child is clothed, nurtured, loved and educated in English and native languages,” she said. “The joy in their faces makes me feel so proud.”

Called Mother’s Voice, the orphanage grew out of the compassion Sjogreen’s mother has always felt for little children, even when Sjogreen was a girl.

"Some mornings we’d wake up and there would be a new face in our house,” she said.

Because Sjogreen’s father worked in nursing, he was able to arrange for free pediatric care, though sometimes the doctors assumed the youngsters were his children.

Sjogreen said over the years the family had to make some sacrifices for the orphans they took in, and, as a teenager, she questioned her mother about taking on the burden.

“My mother just has so much love in her heart,” Sjogreen said, “she had to reach out to these children.”

Since inception, Mother’s Voice has operated with no government support. Some of its revenue is generated by also serving as a day care center, but additional funds are needed to properly care for the orphans.

Sjogreen and her husband, along with her siblings, support the orphanage by wiring money—even small amounts—whenever they can.

One sister, Sarah, works at the orphanage, and even the Sjogreen boys, 10 and 8, express concern about the children. The boys got to see the orphanage 16 months ago when the family visited Ghana.

Though Sjogreen worries about funding, her greater concern is for the future of Mother’s Voice. Her father is 73 and her mother is developing glaucoma, so Sjogreen has plans, as the oldest child, to one day take the knowledge she’ll gain from her college degree and move back to Africa to run the orphanage.

“My desire to save the orphans of Ghana is like an earthquake,” said Sjogreen, her eyes pooling with compassion. “It’s as if I hear my mother’s voice inside me.”

. . .

. . .

. . .

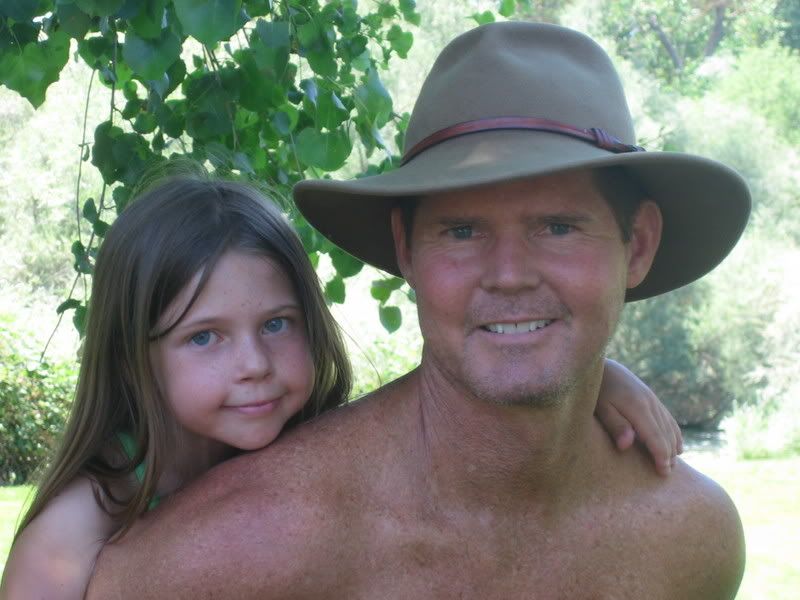

Cathy Sjogreen holds a photo of orphans at Mother’s Voice, an orphanage she helped her parents start in Ghana in 1992.