Jim Ott's Blog

This blog is a collection of columns I've written for Bay Area News Group newspapers serving the East San Francisco Bay region.

This column appeared in the Tri-Valley Herald in March 2006.When Cathy Ayelevi Forson Sjogreen was growing up in Ghana, her parents couldn't afford to send her to high school, so she earned money for her education by selling produce in an open-air market from a tray atop her head.

“I love learning,” said Sjogreen, 40, who speaks ten languages and whose first memory of school is sitting under a tree with other students. “We were taught according to the old British system.”

Today, Sjogreen, who lives in Livermore with her Swedish mathematician husband and their two young sons, hopes to one day return to her country of birth.

“When my husband first got his job with Lawrence Livermore Lab,” Sjogreen said, “my boys and I stayed in Sweden so I could finish my degree at Stockholm University.”

But the boys missed their father so much that Sjogreen moved the family to Livermore six months later, arriving in 2004 with her degree unfinished.

The oldest of seven children, Sjogreen has a special talent for learning languages. While a young woman in Ghana, Sjogreen used her language skills to land a job. Then, over time, her aptitude—and the generosity of a supervisor who paid her air fare—opened the door for Sjogreen to move to France, where she initially lived with an uncle.

"I admire everything about France,” she said, “its language, history, literature, and culture.”

Sjogreen lived in several French cities and worked as an interpreter and bilingual secretary. She also volunteered as a translator in hospitals, airports, train stations, and churches.

Always eager to enhance her language proficiency, Sjogreen was taking an advanced course in French in the early 1990s when she met her future husband, Bjorn.

“He was working on his post doctorate project,” she said. “It took me almost a year to agree to move to Sweden, because I still had my job, my relatives, and my good friends in France.”

Love, of course, won out, and Sjogreen moved to Sweden in 1994.

Now, 12 years and two children later, she hopes to finish her undergraduate degree at the University of California, Berkeley. In the meantime, she is attending Las Positas College.

“My intended major is French Literature,” she said, “but I’m curious about languages and wish to do more research in the field.”

While Sjogreen’s near-term goal is to complete her formal education, her eyes soften when she talks about Ghana and the 120 children her parents care for in the orphanage she helped them start in 1992.

“Each child is clothed, nurtured, loved and educated in English and native languages,” she said. “The joy in their faces makes me feel so proud.”

Called Mother’s Voice, the orphanage grew out of the compassion Sjogreen’s mother has always felt for little children, even when Sjogreen was a girl.

"Some mornings we’d wake up and there would be a new face in our house,” she said.

Because Sjogreen’s father worked in nursing, he was able to arrange for free pediatric care, though sometimes the doctors assumed the youngsters were his children.

Sjogreen said over the years the family had to make some sacrifices for the orphans they took in, and, as a teenager, she questioned her mother about taking on the burden.

“My mother just has so much love in her heart,” Sjogreen said, “she had to reach out to these children.”

Since inception, Mother’s Voice has operated with no government support. Some of its revenue is generated by also serving as a day care center, but additional funds are needed to properly care for the orphans.

Sjogreen and her husband, along with her siblings, support the orphanage by wiring money—even small amounts—whenever they can.

One sister, Sarah, works at the orphanage, and even the Sjogreen boys, 10 and 8, express concern about the children. The boys got to see the orphanage 16 months ago when the family visited Ghana.

Though Sjogreen worries about funding, her greater concern is for the future of Mother’s Voice. Her father is 73 and her mother is developing glaucoma, so Sjogreen has plans, as the oldest child, to one day take the knowledge she’ll gain from her college degree and move back to Africa to run the orphanage.

“My desire to save the orphans of Ghana is like an earthquake,” said Sjogreen, her eyes pooling with compassion. “It’s as if I hear my mother’s voice inside me.”

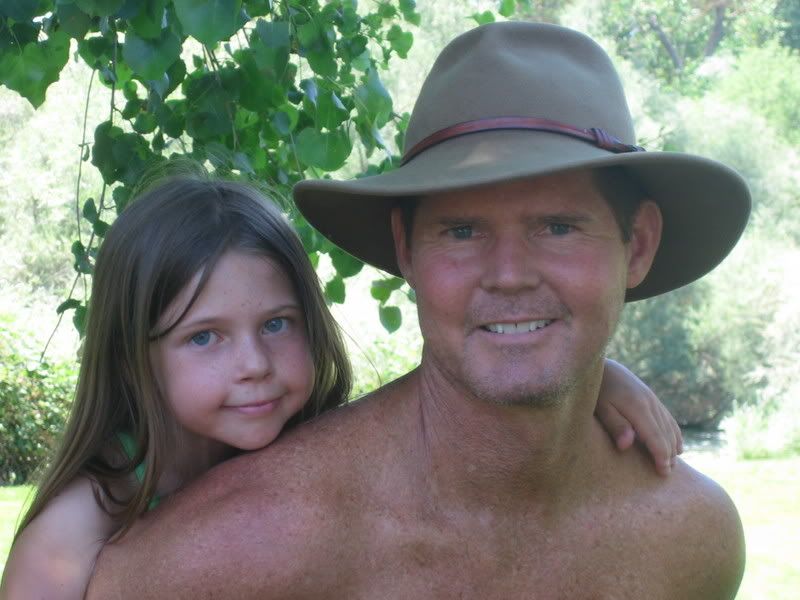

. . .. . .. . .Cathy Sjogreen holds a photo of orphans at Mother’s Voice, an orphanage she helped her parents start in Ghana in 1992.

This column was published in the Tri-Valley Herald five days after Thanksgiving, 2006. Last week on Thanksgiving, I shared with my parents and in-laws a story my 11-year-old daughter recently wrote about a rafting trip we took along the Stanislaus River this past summer. For Kelsey, it’s a tale she needed to write about to get beyond the experience. For me, it’s a narrative brimming with thankfulness.

Kelsey enjoys writing, and has knack for suspense: “Walking over the bridge to go river rafting for my second year, my heart pounded. I could hear Mother Nature’s birds chirping, but what I couldn’t know was that after this journey, I would never dare to even think about rafting.”

She then describes getting instructions from the 20-year-old “radical instructor” who calls everyone dude. She notes the difficulty of climbing into the raft because “I am twice as small as I should be.”

Kelsey is small for her age, having battled several medical challenges and a leaky heart when she was very young. She had open-heart surgery when she was three, and underwent scoliosis surgery after our summer vacation.

Once in the raft, but before launching, she writes how she “bounced around on the sponginess” and sung repeatedly, “I love river rafting!”

Kelsey conjures brief sketches of the family members on the trip. She writes about her stepmother, Pam, saying, “She is always happy. I have never once seen her mad.”

She describes her 14-year-old sister, Melissa, as having blonde hair and blue eyes, and looking just like her mom.

I appear in the story wearing a hat with my fishing license clipped to it, important details later in the tale.

Having set up the scene and characters, Kelsey now builds to the critical moment: “After we got in the river and under a bridge, it happened. We came to it. There was the rapid.”

Below an illustration of a huge blue wave going over the raft, in which a tiny Kelsey with a red life vest is seated on the bottom, she portrays the chaos that follows our plunge “right down the middle” of the rapid.

It’s worth noting that this section of the Stanislaus River, which starts at Knights Ferry, is about as gentle as any river can be. Last year we rafted the same stretch and glided easily through every rapid. This past summer, though, rains caused the river to swell.

“Kelsey, hold on to the boat!” Pam shouts, and a moment later when Kelsey realizes I’ve fallen off the back of the raft, she screams “Dad!!!”

Picture me being pitched into a rushing river. In an instant, I was downriver from the raft, abducted by brute force from my wife and daughters, my head dunking under from time to time, my hat still atop my head, my mind panicked and flooded with thoughts of drowning or breaking a leg or arm.

During all this, 14-year-old Melissa remained calm, certainly frightened, but able to focus on working with her step mom to paddle with strength to catch up to me, to then help pull me from the fast-flowing water. Kelsey’s succinct “after four tries, we got him” understates their heroic success in rescuing me.

The last page of Kelsey’s story describes her tears, how in the aftermath of my rescue she “cried and cried,” how the rest of the trip “was torture.” She also notes that I’d lost my hat in the ordeal, and that my fishing license had been swept away.

Indeed, as we continued down river, Kelsey was almost inconsolable in spite of our efforts to calm her fears. As we coasted smoothly along several long stretches, as Kelsey snuggled next to me, my own silent terror began to give way to a profound joy and thankfulness for life.

Then something magical happened, a sign that all would be well. Kelsey writes how we came upon my hat, just beginning to sink as Melissa snatched it from the river. Then, a moment later, there was my fishing license, floating along in its plastic case, waiting for us to rescue it.

Soon, Kelsey felt better. She even sat near the front of the raft and trailed her hands through the water. When we stopped for a picnic along the shore, she tried her hand at casting and fishing.

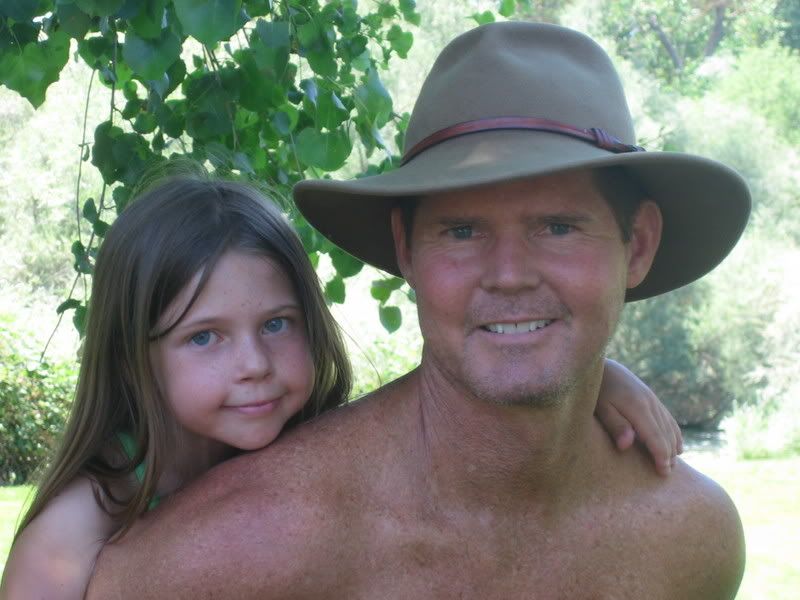

And while at the end of the trip we were thankful to be finished and safe, Kelsey says it best as she ends her tale with the perspective of fifth-grader who has gained wisdom: “The only good thing was it makes a good story, and next year we’ll be doing pottery.”  Feeling better after the trip...

Feeling better after the trip...